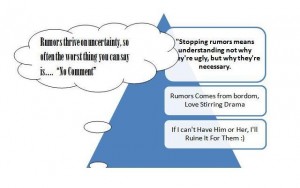

FOR ANYONE WHO is worried about the power of a vicious rumor, the question is why do people do it? We always buffeted by rumors about his religion, that upbringing, controversial statements made by him, or her, and we all know fast false rumor travels?

Fighting rumors by publicizing them in vivid, high-profile locations is, to say the least, a surprising tactic. It’s hard to imagine someone victimized by workplace rumors summarizing them and posting them on the lunchroom wall. The conventional wisdom about rumors is to take the high road and not respond. And yet new research into the science of rumors suggests that it makes sense that rumors comes from a place of misunderstandings both how rumors work and why they exist.

By using the tools of evolutionary theory and new approaches to mathematical modeling, researchers are drawing a clearer picture of how and why rumors spread. As they do, they are finding that far from being merely idle or malicious gossip, rumor is deeply entwined with our history as a species. It serves some basic social purposes and provides a valuable window on not just what people talk to each other about, but why.

Rumors, it turns out, are driven by real curiosity, fear and the desire to collect more information about the other person, group or organizations. Even negative rumors aren’t just scurrilous or prurient – they often serve as glue for people’s social networks. And although it seems counterproductive, these facts about rumor suggest that, often, the best way to help stem a rumor is to spread it. The idea of “not dignifying a rumor with a response” reflects a deep misunderstanding of what rumors are, how they are fueled, and what purposes they serve in society.

Rumor has been around as long as human civilization, and for much of that time has been frowned upon. The Bible has some stern words for those who spread rumors: “A man who lacks judgment derides his neighbor,” the Book of Proverbs reads, “but a man of understanding holds his tongue.” Rumors have long been seen as at best trivial, and at worst vicious and immoral.

Experts began to look at rumors more analytically in the 1940s and 1950s, in a wave of research fueled by concern about how rumors could be managed during wartime. Though interest waned during the following decades, rumor studies have seen a resurgence in the last decade or so – partly because researchers are now more able to tackle complex, dynamic phenomena, and partly because they’re newly armed with the biggest ongoing social psychology experiment in human history, the Internet, which provides them with terabytes of recorded rumors and a way to track them.

In 2004, the Rochester Institute of Technology psychologist Nicholas DiFonzo and another rumor researcher, Prashant Bordia, analyzed more than 280 Internet discussion group postings that contained rumors. They found that a good chunk of the discourse consisted of the participants sharing and evaluating information about the rumors and discussing whether they seemed likely. They realized, in other words, that people on the sites weren’t swapping rumors just to gossip; they were using rumors as a vehicle to get to the truth, the same way people read news.

“Lots of times people will share a rumor not for their benefit or for the other person’s benefit, but simply because they’re trying to figure out the facts,” says DiFonzo, one of the leading figures in the resurgence of rumor research. He published a book on the topic this fall: “The Watercooler Effect: A Psychologist Explores the Extraordinary Power of Rumors.”

Some types of facts seem to be more urgent triggers than others. Rumors that involve negative outcomes tend to start and spread more easily than ones that involve positive outcomes. Researchers sort rumors into “dread rumors,” driven by fear (“I heard your partner is talking bad behind you”), and “wish rumors,” driven by hope (“I heard our holiday bonus will be surprising this year”). Dread rumors, it turns out, are far more contagious. In a study involving a large public hospital in Australia, Bordia and his colleagues collected 510 rumors that could be classified as dread rumors or wish rumors. Four hundred and seventy-nine of them were dread rumors.

Perhaps even more than negative stories dominate the news, negative rumors dominate the grapevine. In the absence of other sources of information, people turn to rumors to answer their most urgent concerns – suggesting that rumors play a vital role, not a peripheral or idle one, in times of worry, and can have a profound impact on how a town, city, or society and an individual reacts to a negative event.

Aside from their use as a news grapevine, rumors serve a second purpose as well, researchers have found: People spread them to shore up their social networks, and boost their own importance within them. To the extent people do have an agenda in spreading rumors, it’s directed more at the people they’re spreading them to, rather than at the subject of the rumor.

People are rather specific about which rumors they share, and with whom, researchers have found: They tend to spread rumors to warn friends of potential trouble, usually out of jealousy but also to make themselves look important as someone who want to help them, while their action would be harmful to spread a given rumor in a certain context or to a certain person.

The psychologists John L. Shelton and Raymond S. Sanders, in documenting the impact of a murder of an undergraduate on the Ohio State University campus in 1972 on the student body, found that those with access to “inside information” about the crime and the administration’s response were instantly granted higher social status. So simply possessing – or being seen as possessing – potentially useful information can serve in and of itself as a motivation to spread rumors.

When it comes to rumors about people rather than events, psychologists have found that we pay especially close attention to rumors about powerful people and their moral failings. Frank McAndrew, a professor of psychology at Knox College who studies the evolutionary roots of gossip, has found that we’re particularly likely to spread negative rumors about “high-status” individuals, whether they’re our bosses, professors, or celebrities.

Our behavior, McAndrew suggests, evolved in an environment in which information about others was crucially important. Back when humans lived in small groups, he theorizes, information about those higher than us on the totem pole – especially information about their weaknesses – would have been hugely valuable, and the only source we had for such information was other people. (McAndrew’s work, much of which focuses on our obsession with celebrity culture, suggests our brains aren’t terribly adept at distinguishing people who are “actually” important from people who simply receive a lot of attention.)

If the fundamental dynamics of rumor have roots that run deep into history, the means of transmission have been changing a great deal recently. Unlike previous forms of media, the Internet has created a two-way street – a way to quickly connect with like-minded people – that greatly multiplies the power of rumors.

So are such rumors impossible to stop? Not at all, says DiFonzo, who has counseled businesses, organizations, and academic institutions on how to fight rumors.

The first and perhaps most obvious point is that it’s futile to attempt to rebut a rumor that’s true, says DiFonzo. Even if it works initially, “people who are interested in ferreting out the facts are really very good at it over time if they have the proper motivation and they work together.”

Anthony Pratkanis, a psychologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who studies persuasion and propaganda, says that an effective rebuttal will be more than a denial – it will create a new truth, including an explanation of why the rumor exists and who is benefiting from it.

But in the case of a powerful rumor that looks like it will spread widely, DiFonzo and other experts say it makes sense to assume it will get out, and preemptively target those who are likely to hear it. When thousands of years of human experience are driving something forward, it doesn’t make much sense to try to push the other way.

Copyright 2012 © All Rights Reserved

November 15th, 2012

November 15th, 2012  doreen.co

doreen.co

Posted in

Posted in  Tags:

Tags:

HMI Private Practice of Hypnotherapy Provider

Primary specialty: Alternative Medicine

Secondary speciality: Behavior Therapy

Doreen is an

Honors Graduate of HMI and also a Certified Practitioner /Facilitator of The Melchizedek MethodT (incorporating the Hologramof Love Merkaba). Energy Healer since August 1999, she was healedfrom a car accident preventing back surgery and being able toeliminate her back pain with hypnotherapy and energyhealing

Doreen is an Honors Graduate of HMI and also a Certified Practitioner / Facilitator of The Melchizedek MethodT (incorporating the Hologram of Love Merkaba). Energy Healer since August 1999,...

HMI Private Practice of Hypnotherapy Provider

Primary specialty: Alternative Medicine

Secondary speciality: Behavior Therapy

Doreen is an

Honors Graduate of HMI and also a Certified Practitioner /Facilitator of The Melchizedek MethodT (incorporating the Hologramof Love Merkaba). Energy Healer since August 1999, she was healedfrom a car accident preventing back surgery and being able toeliminate her back pain with hypnotherapy and energyhealing

Doreen is an Honors Graduate of HMI and also a Certified Practitioner / Facilitator of The Melchizedek MethodT (incorporating the Hologram of Love Merkaba). Energy Healer since August 1999,...